Malawi's rural countryside primary education focus of faculty trip

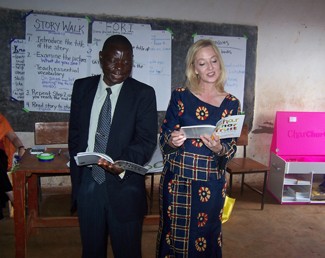

Jennifer Jones with a Malawian Education Advisor.

Only a few miles outside Malawi’s capital city of Lilongwe, the urban landscape gives way completely to the verdant farmland that dominates the African nation. The bush, crisscrossed by a network of rough dirt roads, is home to the villages and farms where the majority of Malawians make their homes.

Called "The Warm Heart of Africa," democratic Malawi is one of the world’s least developed peaceful countries. Despite the material poverty of the former British colony, however, one of the most vibrant forces in the rural countryside is primary education.

With the assistance of an interdisciplinary grant and university support, three Radford faculty members spent nearly a month in Malawian schools on a mission to foster professional development among teachers, promote literacy and the arts and identify and support students with special needs.

"There really is no professional literature on these topics and very limited services for teachers and kids," said Brooke Blanks, an assistant professor in Special Education in the School of Teacher Education and Leadership who initially organized the project. "People write about education in Sub-Saharan Africa from a deficit perspective. When you go and look, you see over and over again that there is great practice here. The problems they have to solve are related to resources and knowledge and we can help fix that."

Blanks was joined by Jennifer Jones, a member of the literacy faculty of the School of Teacher Education and Leadership and Patricia Winter, an assistant professor of music therapy in the Department of Music. The trio set out on their educational mission on May 11 and returned on June 1.

"We spent time in twenty rural schools in two zones outside of Lilongwe," Blanks said. "We went in and we sat on the floor, got our feet dirty and ate with our hands. We know the people. We know the kids."

This trip was the continuation of a research expedition that Blanks took in the summer of 2012. Using RU Study Abroad connections in Malawi, Blanks struck out on her own to get a sense of how special needs children were treated in the country. What she found was a challenging set of cultural preconceptions that were nevertheless beginning to change.

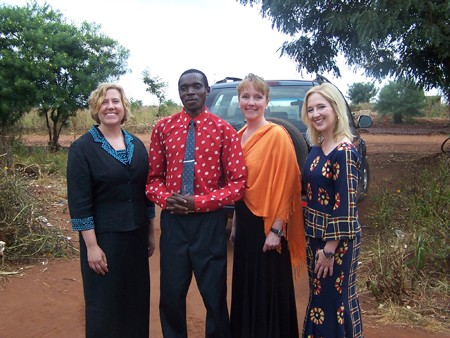

From left to right: Dr. Trish Winter, a Malawian teacher, Dr. Brooke Blanks, and Dr. Jennifer Jones.

"There are stigmas and cultural mores about students with disabilities, that they might not be able to be educated," Blanks said. "But they’re a very politically engaged society. The government just passed a civil rights bill for people with disabilities and last year, in 2012, the Day of the African Child recognized children with disabilities. The work is really timely."

Upon her return to the United States, Blanks realized that there was an opportunity to go beyond helping change attitudes towards special education. She recruited Jones and Winter, experts in their fields of literacy and music therapy respectively, to return and help create a professional development course for Malawian teachers.

The new, expanded project, entitled "Zinthu za za aliyense," which means "Something for everyone" in Malawi’s Chichewa language, was made possible with an internal grant from Radford’s University-Wide Research Award program and support from non-governmental organization The Landirani Trust (now known as African Vision Malawi).

Working with the NGO, the group was able to introduce new books and materials into the schools. For Jones, who has spent her career working to promote and grow literacy, the situation in Malawi presents many unique challeneges.

"In many of these classrooms there might only be one book for ten or fifteen kids but one issue is that when new materials come into the schools there is a hesitancy to use them," Jones said. "The teachers don’t want to mess these books up because they are gifts. One goal was to give them the confidence to use the materials. Like the project’s title suggests, the big emphasis was access for everyone."

A typical public primary school in Malawi might serve 2,000 students in grades one through eight, with a single room for each grade. It is not uncommon for 200 students to pile into a space no larger than an RU classroom. The tin roofs of the schools lack insulation and in the summertime wet season the frequent rains batter so loudly that teachers must halt their instruction and wait for the downpour to cease.

Despite these difficulties, the group was able to introduce the new materials and researched coaching methods into the educational system. Their coaching work with a fairly small number of teachers will eventually impact as many as 20,000 students.

Winter, who recently received her doctorate in music therapy from Temple University, acted as the resident music expert and had the chance to help reconcile Malawi’s artistic and educational cultures. In the classroom, primary school teachers are asked to write songs as part of an expressive arts curriculum. This proved again and again to be a sticking point.

"There were these amazing lessons and wonderful discussion but when we got to the music piece it all stopped," Winter said. "Because it’s a lot to ask someone to write a song. By engaging them in the process and teaching them how to construct a song we were able to offer them tools to help them feel more comfortable with incorporating music.

Although music was a challenge in the classroom, Winter and the others did note that the music was an important part of life in rural Malawi.

"Music is such a part of community functions in Malawi, similar to how it is here in Appalachia," Winter said. "You learn the songs and dances of your culture and they get played over and over again. It’s the thread that binds the fabric of the community together."

The work that Blanks, Jones and Winter undertook in Malawi was locally-focused in a relatively small area, but all three believe it will have a lasting effect on the education of the children affected, both those with and without special needs.

"Radford University has had an impact that is beyond measurable there," Blanks said. "We have 20,000 kids that are going to have a book in their hand this year. We have 60 teachers who now have received professional development using research-based practices in literacy, in music therapy and in special education. It cost a dollar a child."

Blanks won't have to twist her colleagues' arms to get them back to Africa. They plan to apply for more grants that will allow them to continue the work they started in the rural communities of Malawi.

"Next year we'd like to go back, try to narrow our focus and figure out some effective coaching strategies that we can test in the country over time," Blanks said. "It’s one school, one teacher and one kid at a time. One size doesn't fit all in Malawi."

Learn more about Radford University at www.radford.edu.