Biography: Willard Ellery Treat

by Jessica Sosnicki (2008)

The Biology Department at Radford University has a vast set of specimens collected

over the years. Of that collection, Willard E. Treat contributes a small, but significant

part. Born almost a century and a half ago, there is little known about him and why

his collection ended up at Radford University. However, his specimens are still important

to natural history.

Willard Ellery Treat was born on July 31, 1865 in East Hartford, Connecticut, where

he resided most of his life (U.S. Federal Census, 1870). His father, Ellery Treat,

worked in East Hartford as a bookmaker, while his mother, Eunice, was a homemaker.

According to the 1870 Federal Census, Willard had a sister, Adella (“Della”) G. Treat

as well. Although, the Census did not indicate other siblings, he also had two brothers,

William Howard Treat and Edwin Cuyler Treat (Warner, 1902). Around the age of 20,

Willard attended Wesleyan College in Middletown, Connecticut not far from his hometown.

In college, he was a member of Alpha Alpha, a Wesleyan chapter of Chi Psi. The Sixth

Decennial Catalogue of Chi Psi states he was part of the Class of 1888 (Warner, 1902).

However, Willard only attended one year at Wesleyan; he left during his sophomore

year. His two brothers also attended Wesleyan. Like his brother, William Treat left

his second year. Out of the three brothers, Edwin Cuyler Treat is the only one that

actually graduated from Wesleyan, in 1894. Willard E. Treat married on May 4, 1897

to Emma Brooks Shipman. They were married for over 40 years, until she died while

on vacation in Fort Myers, Florida on November 29, 1938. A year later, in 1939, Julia

Lansing Kelsey became his wife (U.S. Federal Census, 1930). They lived on Res 524

Main Street in his hometown, East Hartford, Connecticut. There is no record of her

death. Nancy Finlay, the Curator of Graphics of the Connecticut Historical Society,

stated no children were mentioned in the Federal Census of 1930. According to an article

Nancy Finlay found in the Hartford Courant on July 23, 1922, Willard cultivated 10

acres of tobacco in the Silver Lane section of East Hartford. He had been a tobacco

grower for over 40 years. In the 1895 and 1911 edition of Zoologisches Adressbuch, Treat is also listed as an ornithologist. Another contact, Suzy Taraba, Wesleyan’s

University Archivist and Head of Special Collections of the Olin Library, discovered

that Willard Ellery Treat died on May 9, 1955. This information was found in the Alumni

Record of 1961, although Willard did not graduate from Wesleyan. In the 1952 edition

of the Wesleyan University Alumni Record, more is stated about Willard Treat:

“Treat, Willard Ellery. Chi Psi. b July 31, 1865, East Hartford. Left fr yr; tobacco

grower 1897-1923; mem Am Ornithologist Union 1886-1904; taxidermist 1882-1930; pub

articles on outdoor life; m May 4, 1897 Emma Brooks Shipman who d 1938; m Julia Lansing

Kelsey 1939. Red 524 Main St, East Hartford.”

Even with this information, it is difficult to uncover more in-depth information on

his background. One thing is for certain, Willard died in a place he rarely ventured

from during his life, East Hartford, Connecticut.

Life as an Ornithologist and Author

Willard Ellery Treat started his interest in ornithology at a young age. He was a

member of the American Ornithologist Union (AOU) from 1886-1904. During this time,

Willard published a series of small articles in The Auk. All of the specimens described in The Auk were found in Connecticut. In addition, he also published an article in Science titled ‘Great Horned Owls in Confinement’ in 1893. This article showed that Willard

could author nature journals with fine detail and observation. Willard is also cited

in The Birds of Connecticut (1913) by John Hall Sage, Louis Bennett Bishop, and Walter Parks Bliss. He is mentioned

several times throughout the publication where he observed and helped identify birds

for the authors. These birds include the double-crested cormorant, pintail, ruddy

duck, among others. One bird Willard collected, the yellow-headed blackbird, was given

to John H. Sage for his collection in Portland, Connecticut.

Treat Specimens

Although little is known today about Willard E. Treat, his specimens can found in

a number of places. The University of Connecticut holds over 1900 animal specimens,

most of which are birds. As described on the university’s website, “The collection

began with the donation of study skins, (dated between 1875 to 1925) from the private

collections of J.H. Sage and W.E. Treat, and emphasizes the fauna of Connecticut and

the northeastern U.S.” (University of Connecticut, 2004). Susan Hochgraf, Vertebrate

Collections Manager of Biological Research Collections at University of Connecticut,

found two of Willard’s ledger books. The first volume is dated January 1, 1887, a

year after he left college. In this ledger, he included dates, specimen numbers, Latin

names, sex, body measurements, stomach contents, and remarks strictly on bird species.

In the first page, he signed his name, followed by his location, East Hartford, CT.

In addition, there is a small note, stating the donation of some of his specimens

to California, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York. The second volume includes the same

field data, but with mammals, such as bats and shrews. This volume is dated January

1891 through 1915. The meticulousness of Willard’s ledgers shows he was a true naturalist.

The Smithsonian Museum of Natural History houses a very small collection of Treat’s

specimens, which includes a song sparrow, four sharp-tailed sparrows, and a redstart.

James Dean, Collection Manager of the Smithsonian Institute’s Division of Birds, indicated

that all six specimens were collected in the 1890s.

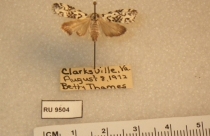

Radford University has a small collection of 29 Willard Treat’s bird specimens, none

of which are on display. All of the specimens were collected between 1885 and 1896.

The specimens include: one cedar waxwing, one rose-breasted grosbeak, two common redpolls,

three common grackles, two brown-headed cowbirds, three rusty blackbirds, two Swainson's

thrushes, two American pipits, one black-capped chickadee, two cerulean warblers,

two northern parulas, one yellow-rumped warbler, one American redstart, one red-breasted

nuthatch, four white-breasted nuthatch, and one ruby-crowned kinglet. There is still

no explanation as to why Radford University houses these specimens. No written documentation

has been found indicating donations from Willard, the University of Connecticut, or

the Smithsonian.

Works Cited

- [1870] U.S. Federal Census (Population Schedule), East Hartford, Hartford County,

Connecticut, (Treat household).

- [1930] U.S. Federal Census (Population Schedule), East Hartford, Hartford County,

Connecticut, (Treat household).

- Askins, R. (2002). Restoring North America's Birds: Lessons from Landscape Ecology.

New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Boyle, W. (2002). A Guide to Bird Finding in New Jersey. New Jersey: Rutgers University

Press.

- Department of Environmental Protection. (2008). Endangered, Threatened and Special

Concern Species in Connecticut. Retrieved October 12, 2008, from Department of Environmental

Protection site: http://www.ct.gov/dep/cwp/view.asp?a=2702&q=323472&depNav_GID=1628

- Sage, J. H., Bishop L. B., & Bliss W. P. (1913). The Birds of Connecticut. Hartford,

CT: The Case, Lockwood, & Brainard Co.

- Treat, W. E. (1893). Great Horned Owls in Confinement. Science, 22, 137-139.

- University of Connecticut (2004). Biological Collections: Bird Collections. Retrieved

September 12, 2008 from

http://collections2.eeb.uconn.edu/collections/birds/birds.html